Teaching Beat Board Techniques

July 11, 2024

This article will cover strategies for teaching Beat Board techniques to use as a tool in your classes on scriptwriting. For more comprehensive information on how to use the various functions of the beat board and story map, please check out this video.

A writing teacher faces many challenges in a classroom. Teaching someone a skill is never simple or necessarily straightforward. That’s why we make lesson plans based on a combination of best practices and real-world experience.

Scriptwriting has its own unique challenges. Not only do you have to teach all the facets of writing with all that entails, but you have to teach students logic in order to do story flow properly. In a script, given the real-world limitations of the craft, that is particularly daunting.

Novelists can have hundreds of pages of involved prose; scriptwriters are typically limited to one hundred or so pages to tell a complete and compelling story, and those pages are a lot less dense than any book.

To accomplish this difficult task, embrace the concept of a Beat Board.

Read More: How to Use a Beat Board for Pretty Much Everything in Your Script

What is a Beat?

We will be breaking down various examples to illustrate the concept of beats and the use of the board but basically, a beat is a character, plot, or sometimes a thematic point you’re trying to make in a script.

Any James Bond film has an opening gambit to set the tone and the character’s skill set. The entire gambit, which is many times not actually connected to the main story, is a beat. It may be multiple moments/scenes internally but it’s that one point you’re trying to make.

The “Quantum of Solace” opens with a bravura car chase scene where Bond in his Aston Martin is being chased by some baddies in an Alpha Romeo. The chase goes through many permutations and scenarios but on a beat board you might only put:

1/ OPENING GAMBIT - Intense Car Chase, Sienna, Italy

The chase takes up four minutes and lots of different locations which are not necessary to put on a beat board. The individual moments of the chase make up the whole. For the purposes of detailing the story’s structure, one ‘master’ beat is enough.

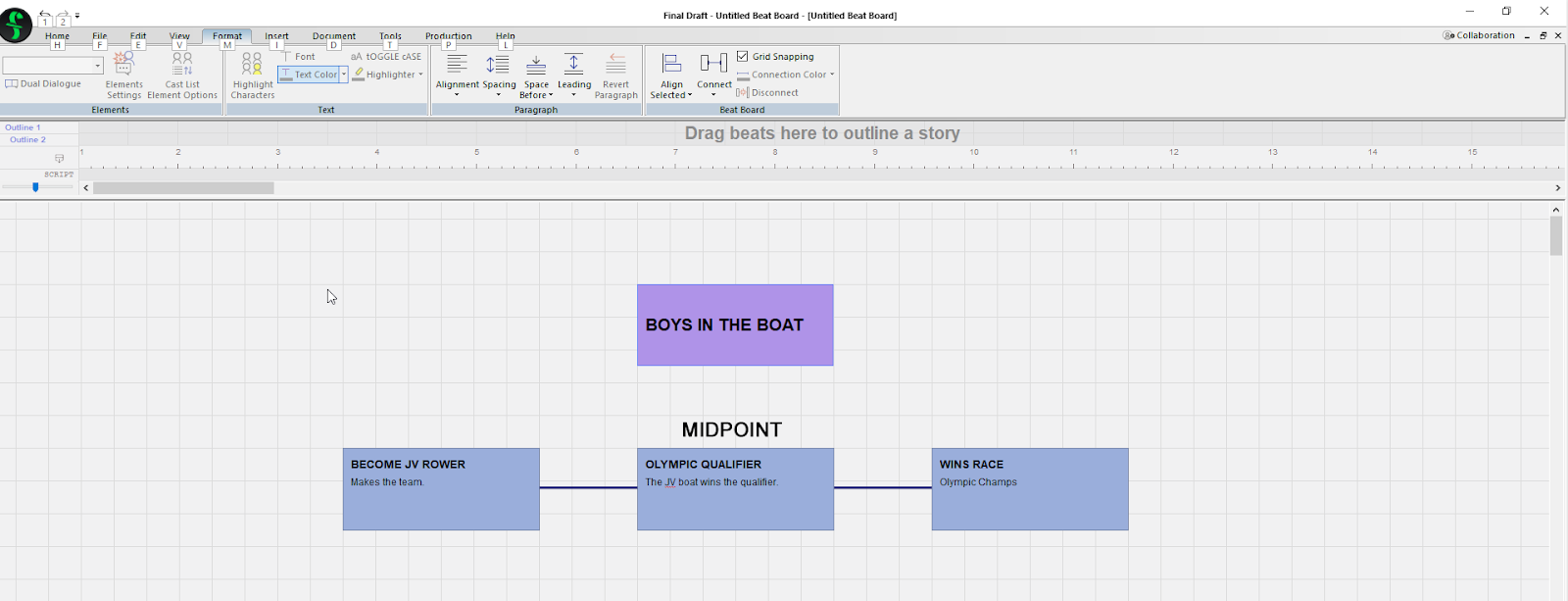

In “Boys In The Boat” the qualifying race that determined that the Washington State JV boat would represent the U.S. in the 1936 Olympics is a tentpole beat. It’s midpoint. Again, the details of that race, the push-pull and drama aren’t necessary to detail initially on the beat board because we’re only showing that beat to finish the first part of Act II

Act I - Become JV Rowers

Midpoint - OLYMPICS QUALIFYING RACE - University of Washington boat wins.

Act III - Win Gold

Boys in the Boat, fig. 1

Speaking of tentpoles, they are structural moments that tie beats together. Depending on whose structure you use, there can be anywhere from seven to a dozen tentpoles of varying importance.

For more on structure see “Save The Cat”, Truby’s “Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller” or the recently released “Quantum Scriptwriting.”

When to Beat

There is no specific answer to this besides tentpoles (which are automatically considered beats) because a beat can be structure, character, or a thematic expression. It depends on how much detail you want to put into a script’s planning.

I tell students to worry about the major structural beats, the tentpoles, first and then fill in the rest as they go along. Once you have a framework of Act I, II, and III you can begin to flesh out the details. So, you can do ‘big picture beats’ or drill down into the nitty gritty. Allow your students to find their best paths as they explore their writing processes.

A beat board changes. It’s dynamic. In a writing room that old index-card-on-a-bulletin-board model was done to be able to shift ideas in and out. Seasons were indicated by title cards and a great idea for a change in direction might go up on the board in season one but ultimately be shifted to season two determined by an unexpected concept that comes up. Beats of that nature might also adapt to social media feedback where audiences are giving the show their undiluted opinions.

In-class exercise: Have students create an old-fashioned beat board in the classroom. Give them paper index cards and have them take turns putting beats up wherever they think they belong. A visual representation of the story will soon take shape. If possible, have them switch the cards around to show the dynamic nature of a beat board.

As an example of the shifting nature of a beat board, back in the day before the social media that increasingly drives our lives, the 80’s sitcom “Happy Days” found an unexpected star in Henry Winkler’s Fonzi. Intended to be a minor character, as he became more popular the season’s episodes shifted to feature and take advantage of that popularity, and entire storylines were built around him. The bulletin board’s index cards in the writer’s room changed dramatically.

Final Draft’s internal beat board allows you to do this digitally as you create. The timeline feature above the index cards gives you an easy-to-see layout on the shape of the storylines. We’ll talk about this more when we get to the “Arrival” breakdown.

Homework exercise: Give students a simple storyline, i.e. princess defies her parents and sets out with her posse to save her brother, the prince, and see what story beats they come up with. Have them place at least seven broad beats either in a linear list or actually use the beat board to begin to frame out the story.

A typical beginning and end point to beat out to would be:

1/ Prince is kidnapped (starting beat).

2-10/ Story beats in-between that lead to:

11/ Princess defies King, goes on dangerous quest (Act I end/Act II beginning).

Why Storyboards/Beats?

Perhaps the hardest thing we as scriptwriters do is tell a story in the restrictive format of a script. You may think Jonathan Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is a long sit - and it is - but the amount of time in the physicist’s life that Nolan had to cover was massive. “Oppenheimer” could have really been a six-episode miniseries given how complex the character was and how volatile and deep the political situation was at the time.

It’s breaking down the structure of the main segments that helps tame this beast.

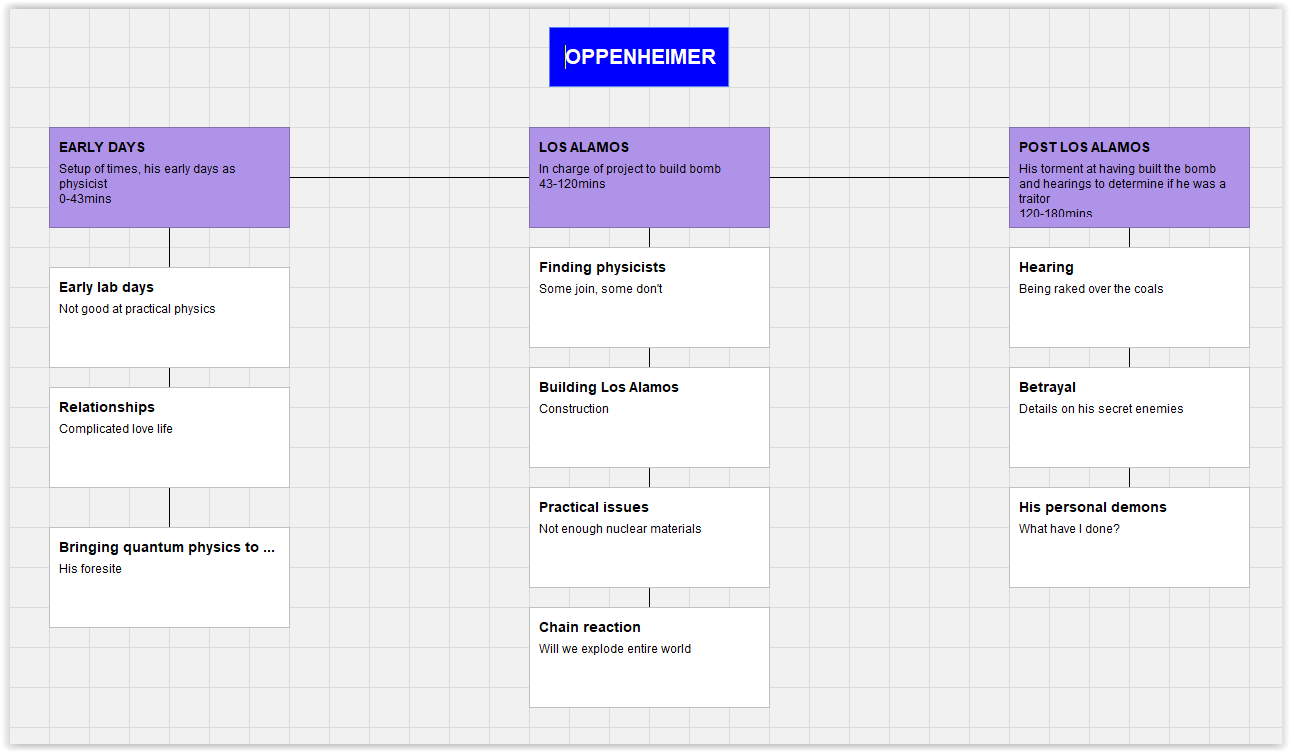

If I was beating out this movie, I’d first split the story into three parts:

1 - Before Los Alamos.

Setup, early days in Oppenheimer’s life.

2 - During Los Alamos.

(biggest, most important segment)

The enormous pressures he faced.

3 - After Los Alamos.

The nightmares and blowback he experienced.

Which is pretty much the way it went.

Certainly, the most interesting and dramatic part of “Oppenheimer” was the Los Alamos story but understanding Oppenheimer, and the fallout from his sometimes roughshod approach to administration, and his nightmares of what his team accomplished - a milestone (good and bad) in history - are vitally important to the movie.

Beating this in more detail under those major headings would provide a nice framework around which to write scenes.

Oppenheimer, fig. 2

If you have ten-fifteen beats, moments of importance that turn the story in a different direction and/or intensify it, then you’ve got a good start as to what to fill in between beats.

You’re also aiming for a specific endpoint goal and that will make a cogent story.

The Beat Board Organizes

A Beat Board is a great organizing tool.

It’s fundamentally a mindmap but Final Draft’s beat board is more flexible and easier to visualize. Almost anything you want can be put on the board including text, images, and script excerpts! Wow. It’s like dumping a set of ingredients in a bowl but having them go together automatically. And if one ingredient doesn’t fit, you move it - easily.

Given how information- and story-heavy the movie “Oppenheimer” was, Nolan needed a way to keep things on track. I’m not sure of his process but the concept of beat boards makes even the most complicated story digestible.

For example, you can color-code the beats so that they are reflected in what third of the story the beat went. Then you can visually connect those beats to other beats with a line (like a mindmap). Students, being so visually oriented these days, can instantly see the logic of this.

Likewise, general categories could be color-coded to show what type of beat they were and where they fell.

- Blue: Physics (simple explanations)

- Sub-beats: quantum physics / black holes / nuclear theory

- Green: Oppenheimer’s ascendancy in the scientific community

- Red: Interpersonal relationships.

- Sub-beats: wife/mistresses

- Friends

- Work colleagues

- Yellow: Thematic overlays.

- Sub-beats: agonizing over responsibilities / the arms race

- Purple: The progress of the making of the first bomb.

- Sub-beats: enriched uranium stores. They do this by using a fish bowl with marbles in it. It shows progress in a very nice visual way

- Etc.

The drilling down of these color-coded beats starts with a generalized framing of the big picture (the trio of broad structure) and continues as you add other beats below those broad categories.

And since students can visually parse a story’s framing it can help them understand the story-telling process.

The great thing about beats is they can just be a moment - you’re not committing an entire act to them (unless you’re writing to a tentpole.) If the beat doesn’t work just move it or delete it.

Beat Boards Teach Organization

Getting beats down on the beat board helps to free your students. Rather than becoming a burden, it’s a simple, visual aid to show students the flexibility and visuality (I know, that’s not a word) of beats.

From years of experience, I know how students struggle with storytelling. Not simple stories; we are indoctrinated into simple stories as children. And not shorts like you see on TikTok or Instagram with a six-second payoff. I’m talking about 100+ pages of script or even a TV series that might have ten, one-hour episodes. That’s a lot to keep track of and most students don’t have an understanding of how to do that.

There are so many factors to keep track of in a longer form. When I’m creating something I keep notes about future beats and dump them onto the beat board. This helps me remember them and see where they go in a way that doesn’t clutter my brain. The process allows you and your students to organize in a different way than plain text.

The Logic

Programmers and lawyers (I primarily teach adults) are the stars of my scriptwriting class for one reason: logic - well two: they are also goal-oriented. These professions especially demand logic and an endpoint. No programmer sits down to create a piece of code without a goal. Lawyers have to present a logical flow to any case they have whether it’s defense or prosecution.

So, they get the logic of storytelling, especially the storytelling of a script that has only so many pages to accomplish its story.

Act I is where a lot of this gets accomplished.

The Wizard of Oz

“The Wizard of Oz” has about as fine a first act as any I’ve seen. And you can do this with your students to show them perfectly how it’s done. Let’s beat it out.

- Dorothy is in trouble, running away from something.

- Her fears are dismissed by her aunt and uncle and the farm hands isolating her.

- She sings of her longing to go “over the rainbow” to run away to a place where she is loved and appreciated.`

- Wicked witch of a woman arrives and takes away her dog to be destroyed.

- Toto escapes, Dorothy runs away from home.

- Meets (fake) Wizard who tells her to go back home because Aunty Em is worried about her.

- Tornado rips house from foundation and takes her over the rainbow.

- She arrives in Oz, accidentally kills Wicked Witch of the East.

- Meets Glenda, munchkins, Wicked Witch of the West, ruby red slippers.

- Yellow Brick Road. Magical journey to discovery.

- End Act I, begin Act II

Wizard of Oz, fig. 3

Notice, and this is important to emphasize to your students, there’s a starting point and end point (in blue). In between are the beats needed to do Act I properly in broad categories. You can show them how to rough out a narrative thread that connects the story beats to one another.

Everything in that first act is necessary to establish and reveal Dorthy, her life, her dreams, and her inner and outer journey.

Exercise for students: Take a movie or the first episode of a TV series and create a beat board. Seeing it done on a successful production makes it easier to do on their original material and increases their understanding of creating a narrative thread.

Big Picture

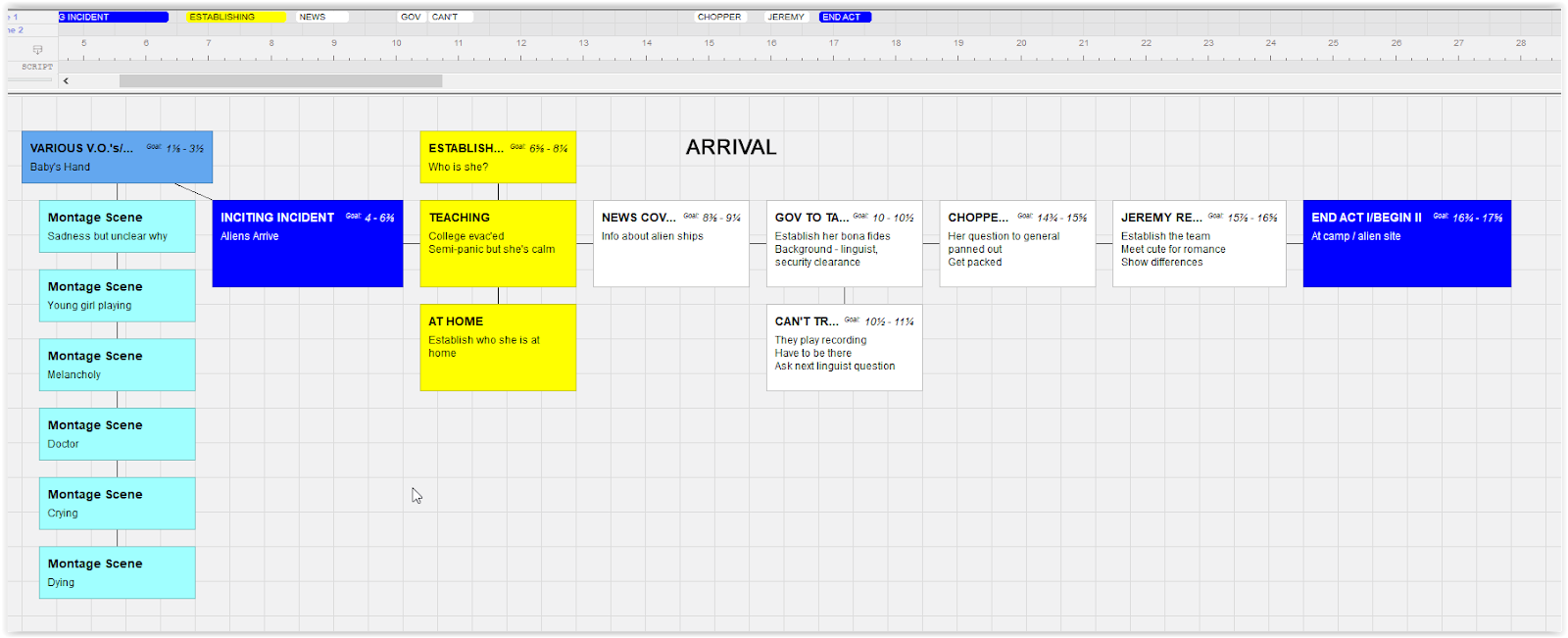

“Arrival’ tells a story of first contact with an alien race. The aliens’ agenda isn’t exactly known but they don’t appear to be inherently evil.

In order to explore their intent, linguist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams ) has to learn their language which is not only visual but has an entirely different aspect to it - the ability to see everywhere at once, shifting timelines without issue.

In the process of learning the heptapods’ language, Dr. Banks will gain the ability to see into the future because her linear perception of time has been altered and she sees all timelines at once. This will help her avert a world war and is the purpose of why the aliens came to Earth.

This is particularly disturbing because she can see the death of a daughter she has yet to bear. By participating in this process, she will experience what no parent should. And she will have to live with that terrible knowledge for decades as her daughter’s death date approaches.

Most of the above isn’t known to the audience when the story opens. But some of it is foreshadowed in disconnected, foreshadowing scenes in which Banks talks to her daughter in a diary.

Many things have to be set up because the ‘A’ story is the aliens' arrival and subsequent communication. The ‘B’ story is there in the form of these foreshadowing epistolatory voiceovers about events that happen in the future.

Even given the complexity of the science behind the linguistic concepts, “Arrival” has a fairly straightforward Act I. We’ll cover the major beats (in bold.)

Beat Sheet in List Form for Arrival

- V.O. MONTAGE, various moments foreshadowing the story’s non-linear nature and theme.

- Her with baby’s hand.

- Sadness but we don’t know why.

- Young girl playing.

- Melancholy.

- Doctor.

- Crying.

- Dying.

- BANKS: But now I’m not sure I believe in beginnings and endings (important theme/plot element)

- 5/ Present day

- BANKS: There are days that define your life beyond your life like the day they arrived

- Teaching at college.

- Establish her normal world.

- 7/ Aliens’ arrival on news during class.

- Alarm - evacuating college.

- Semi-panicky responses but she remains calm, illuminating her character.

- 8/ At home.

- Talking to her mom.

- News coverage.

- 12 ships in all, spread all over globe.

- Sleepless night.

- No one in class or on campus the next day.

- 11/ Government to talk to her.

- She has previous Army intel experience

- Still has top-secret clearance

- Something for her to translate

- Aliens speaking

- 13/ Can’t translate - have to be there.

- They can’t (won’t) take her to Montana

- She gives them a question to ask another linguistics expert

- Ask him Sanskrit word for war and his translation

- 15/ Chopper arrives.

- Expert says war mean argument

- She says it’s actually: a desire for more cows (go to war for that)

- Establish her stunning knowledge

- Pack your bags

- 16/ Jeremy Renner on chopper (their ‘meet cute’ moment).

- Quotes her book/paper - it’s great even if it’s wrong

- Cornerstone of civilization isn’t language it’s science

- He’s theoretical physicist

- Anxious to ask aliens questions

- How about we just talk to them before we start throwing math problems at them?

- Her practical nature

- Team in place / their dichotomy.

- This is why you’re both here (Forest Whitaker character)

- 17/ At site of alien ship and military encampment.

End Act I

I’ve put the opening montage which takes place at various points in the future, in a long vertical line (in teal). This is to show the ability to build substance into a storyline along a beat. The entire montage is a beat called MONTAGE but the individual choices can be anything. The writer can move them in and out as necessary.

In this case, the writer decided to show the entire, sad story of the character’s daughter. We won’t have a complete understanding of the impact of this until almost the very last scene.

Arrival, fig. 4

Also, note the linear timeline at the very top of the image. Those beats were dragged directly from the beat board to the timeline and can be shifted around as needed.

Exercise: Give your students only an endpoint and have them create the beats to that endpoint.

In Conclusion

The Final Draft beatboard offers so many incredible features to make your teaching simpler and more fulfilling for your students.

There are interconnecting tools and techniques with the beat board including the ability to drag text from a script, images, etc. And also have beats transported directly to the script itself.

The main purpose of this article was to show some techniques to begin to train your students to think in a logical storyflow to help create a seamless narrative.

This is how the pros do it either in a film or a TV series writing room. Teaching your students to utilize this tool and its logic will go a long way to preparing them for any writing situation they may face.

Written by: Mark Sevi

Mark Sevi is a professional screenwriter, screenwriting teacher, and podcaster. He is the founder of the Orange County Screenwriters Association.- Topics:

- Writing & Tools