Let's Talk About Parentheticals

April 2, 2019

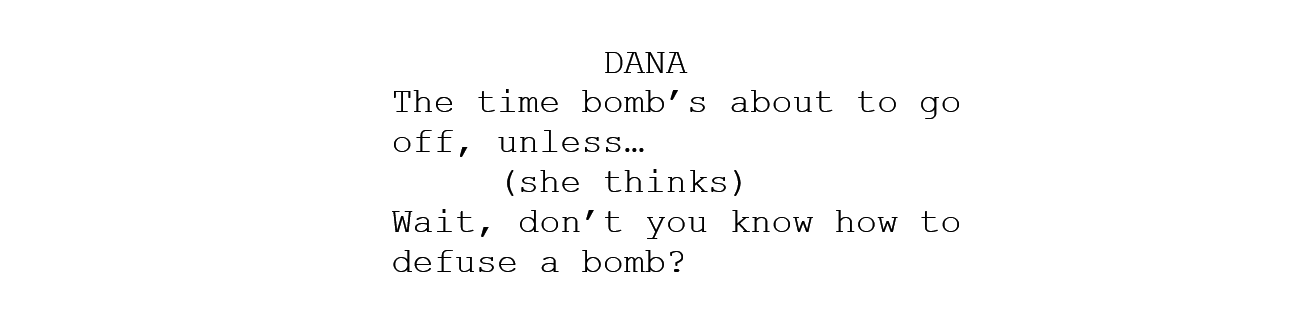

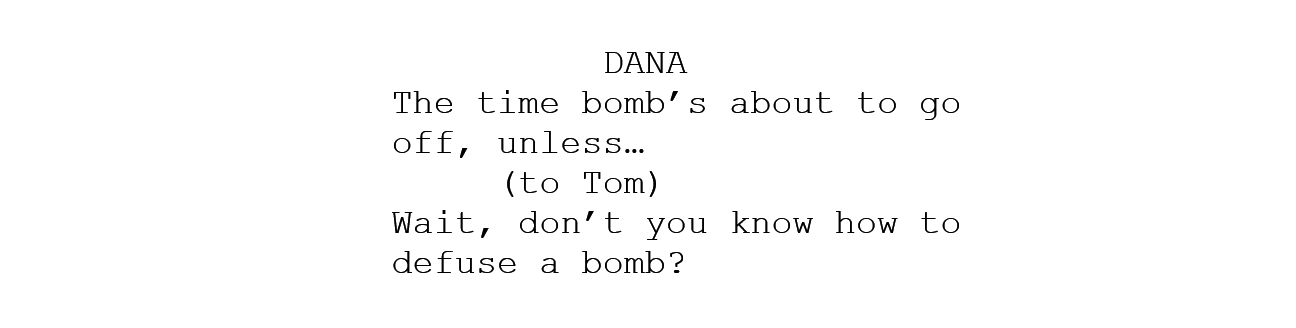

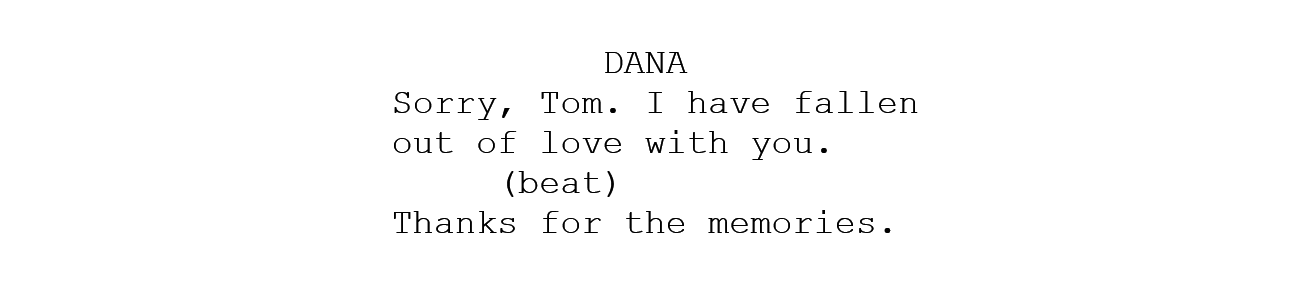

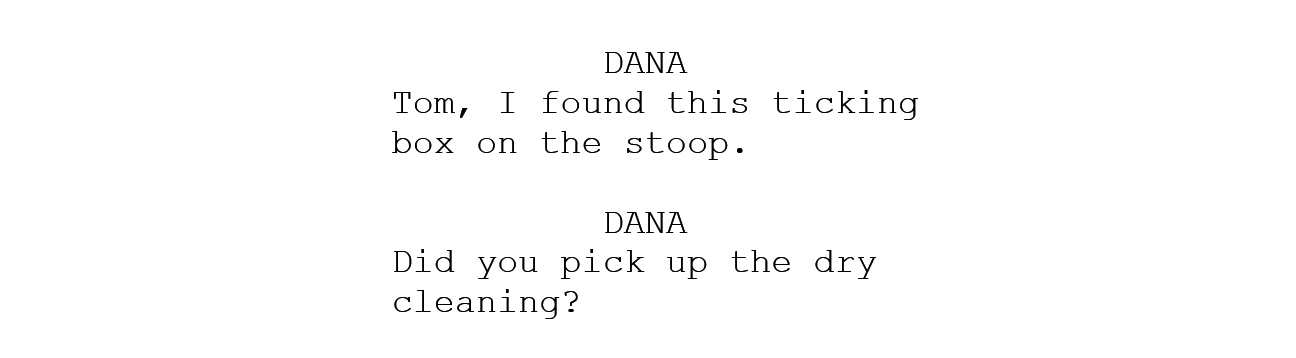

If there’s any element of screenplay format that seems to cause confusion most frequently, it’s the parenthetical. I’m talking specifically about the words that appear between parentheses in the middle of dialogue. First, let’s look at how they should be formatted:

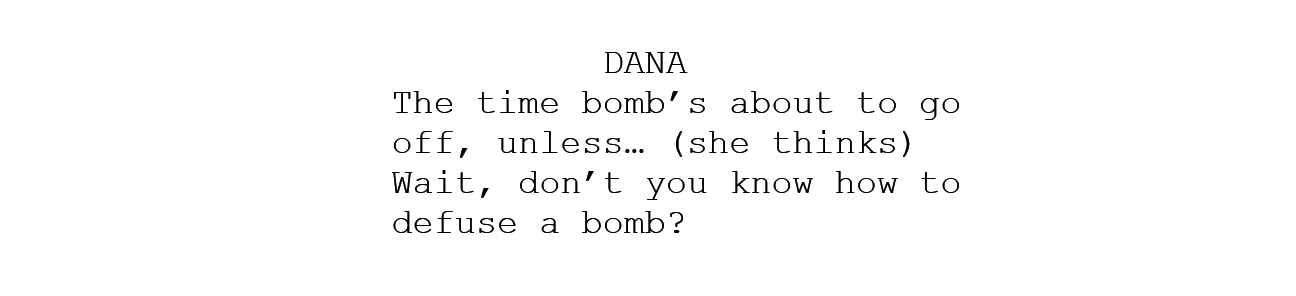

That’s parentheticals 101: they always get their own line. Sometimes, we see the them lumped in amongst the dialogue, like this:

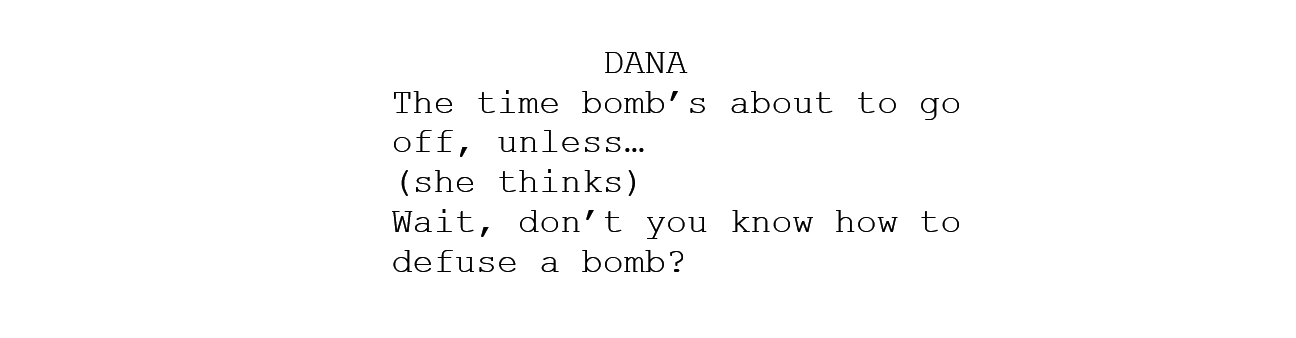

This is incorrect. As is when we see them flush with the dialogue:

Parentheticals are always indented 3” from the left, 5.5” on the right.

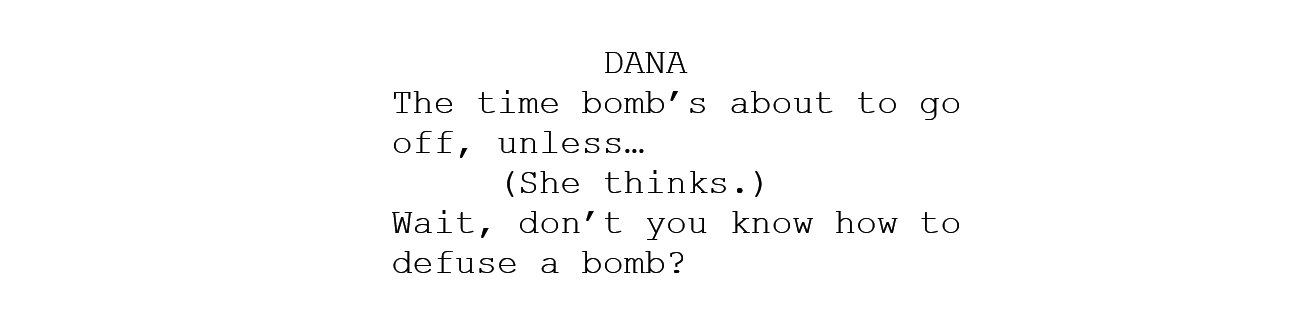

Other times, parentheticals are treated like normal sentences complete with proper grammar:

But this is also incorrect. Parentheticals are always in lower case, with the exception of proper nouns. For example:

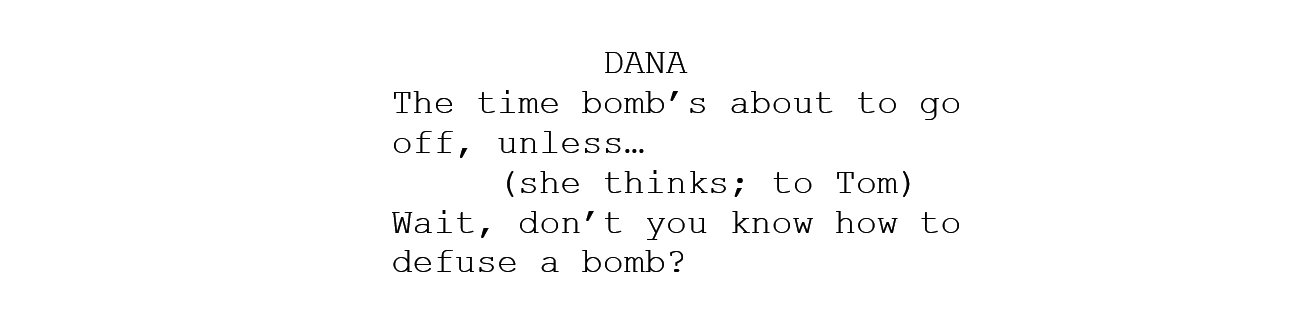

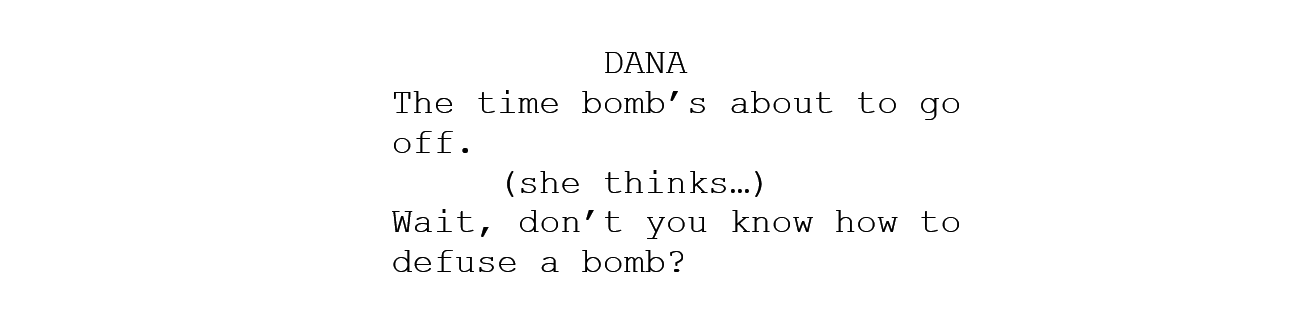

Parentheticals never end in punctuation. Usually, the only punctuation we should see in a parenthetical is a semi-colon separating two thoughts—and even this is rare.

Though sometimes, a script can sneak ellipses into the parenthetical to imply a bit more of a pause, or to underscore open-endedness.

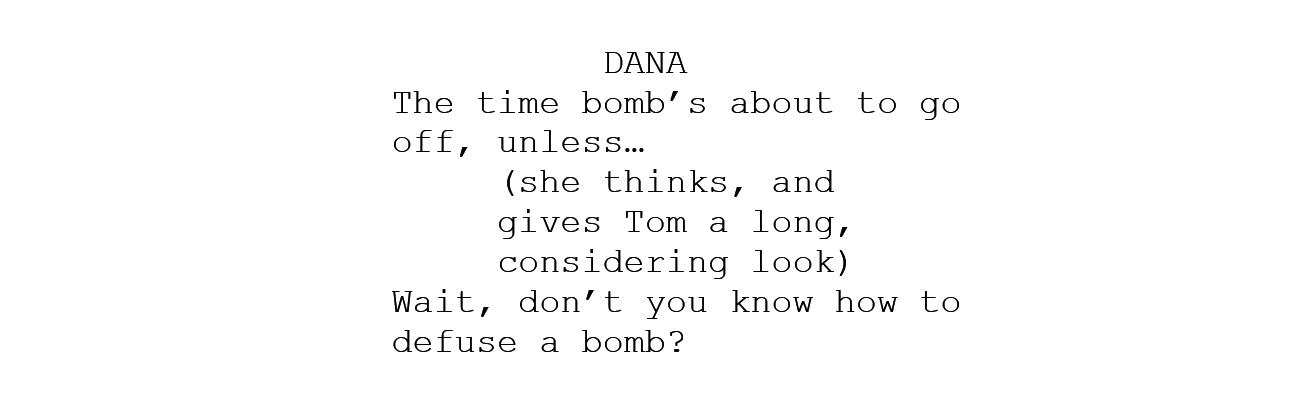

Parentheticals should be short, no more than a handful of words. This is probably too long:

Shorten when possible, and if it can’t be, break it out into description, like this:

As a rule, only use a parenthetical if it’s needed in order to understand the read on the line. For example:

Parentheticals can be used in the same way that novels use adverbs, to tell us how the character is speaking, whether it’s needed or not:

But it’s really best not to clog up the read with a ton of unnecessary parentheticals like this, and may likely be ignored by the actors, anyway.

Similarly, avoid redundancy. For instance:

We know Dana’s raising her voice thanks to the exclamation point, rendering the (shouting) parenthetical redundant.

Parentheticals are also sometimes used to inform the reader to whom the character is speaking. We should only get a parenthetical if it isn’t obvious from the lines themselves. For example, we don’t need the parenthetical on:

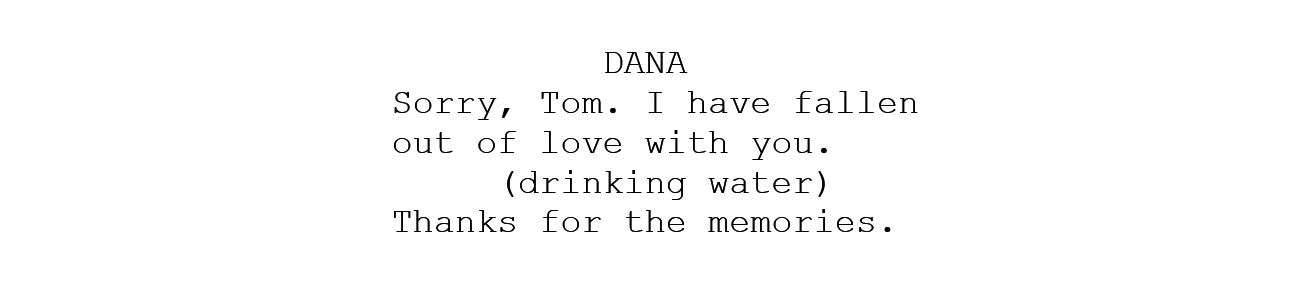

Parentheticals can be used in place of an action line, but the rule still applies that they should be short.

Killing a character is pretty major and should be separated out into its own action line. Thus, don’t use a parenthetical to relay major actions or plot beats. There is often some misunderstanding in terms of how beats and parentheticals work together. Sometimes, a script doesn’t know where or how they should appear, so it throws them all in.

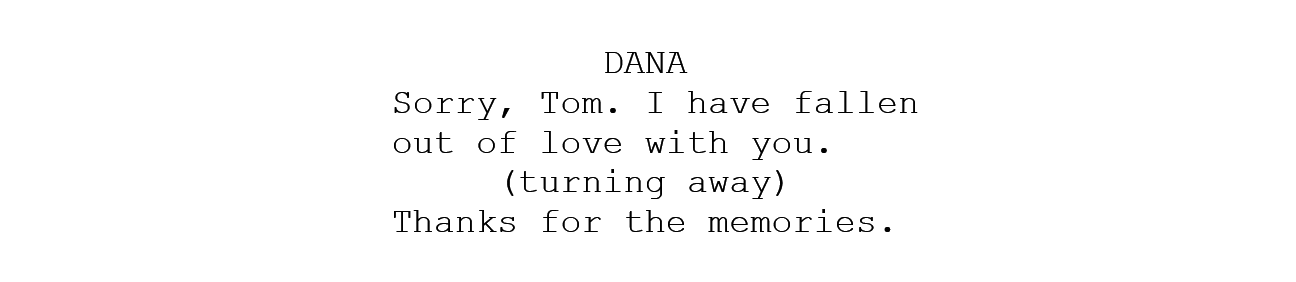

Dropping a beat on the page is fine, though it’s a bit old-fashioned. And all a (beat) tells us is the character is doing nothing for a short period of time. We’re literally burning a line on nothing.

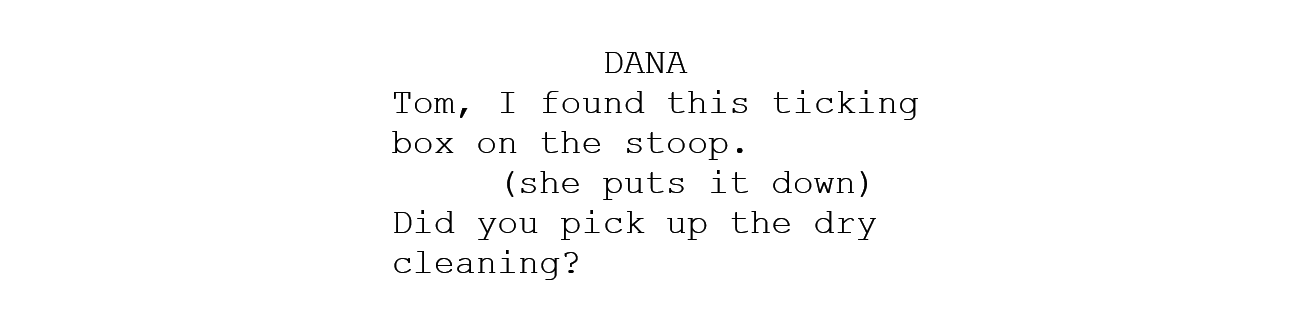

If the idea is to break up dialogue in order to carve out a dramatic moment, or give them a moment to think or react, it’s almost always better to give them a small action or gesture. For example, compare:

…with…

The key is to give the character a gesture or action that has some meaning. Just dropping a random whatever into the dialogue is worse than even the neutral (beat), since it usually comes across as empty or a bit silly.

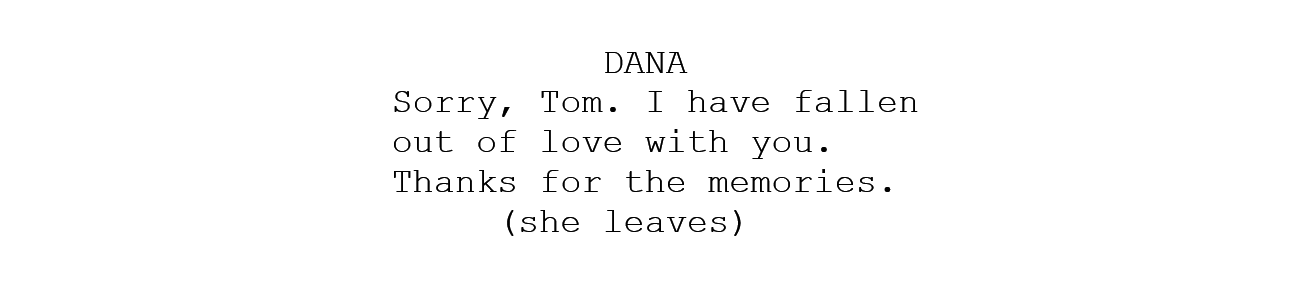

And never end dialogue with parentheticals.

In this specific case, her leaving should appear in a description line. The reason something appears as a parenthetical as opposed to description is because it is inherently tied to the dialogue in some way.

Sometimes, a script will re-attribute the dialogue in order to reflect a beat, shift in focus, or change of subject.

Use a parenthetical for this kind of thing:

It’s good to break up dense bricks of dialogue, and small actions and gestures are a fine way to do that. But it’s very easy to go overboard; don’t chop up dialogue with a bunch of looking, turning, smiling, hand-waving, etc. Less is more.

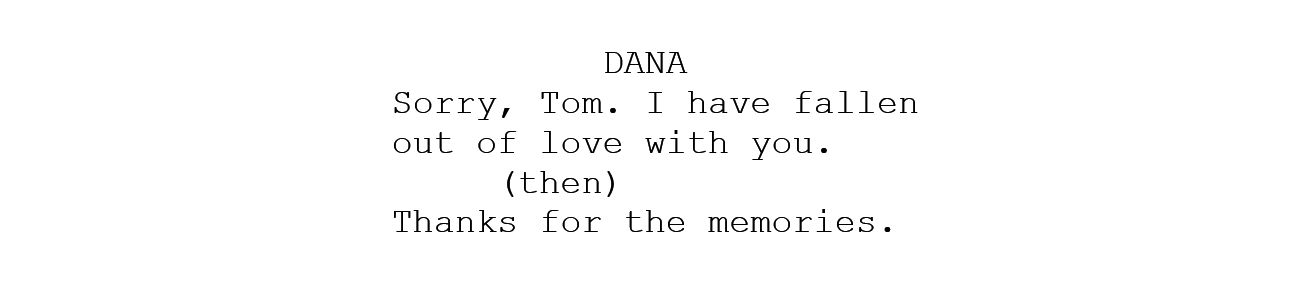

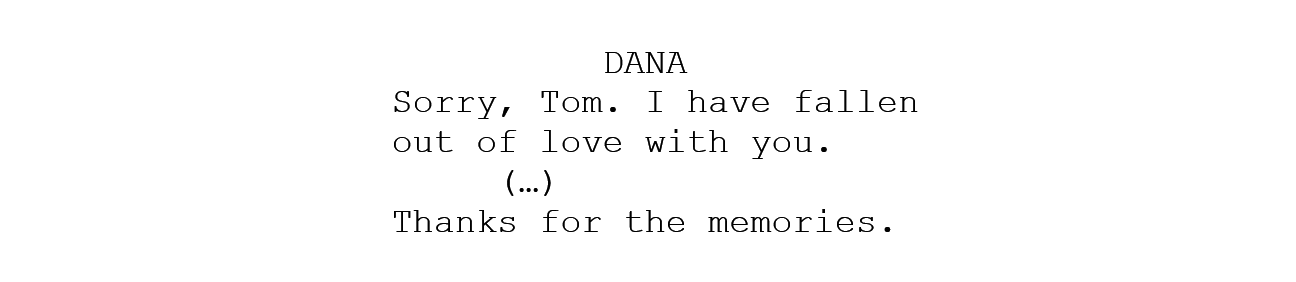

Sometimes, a script will insert little parenthetical gear shifts with an (and) or (then):

Other times, a script will borrow a device from comic book writing and use an ellipses:

Either of these are fine.

That’s your parentheticals crash course for the day. While they are definitely an important part of the screenwriter’s toolbox, as with every other aspect of the craft, they should be used correctly—or not at all.

Written by: Michael Kuciak

Michael Kuciak is the writer-director of the forthcoming horror film DEATH METAL. He's from Chicago.- Topics:

- Discussing TV & Film